The design of an operating system architecture traditionally follows the separation of concerns principle. This principle suggests structuring the operating system into relatively independent parts that provide simple individual features, thus keeping the complexity of the design manageable.

Besides managing complexity, the structure of the operating system can influence key features such as robustness or efficiency:

The operating system posesses various privileges that allow it to access otherwise protected resources such as physical devices or application memory. When these privileges are granted to the individual parts of the operating system that require them, rather than to the operating system as a whole, the potential for both accidental and malicious privileges misuse is reduced.

Breaking the operating system into parts can have adverse effect on efficiency because of the overhead associated with communication between the individual parts. This overhead can be exacerbated when coupled with hardware mechanisms used to grant privileges.

The following sections outline typical approaches to structuring the operating system.

A monolithic design of the operating system architecture makes no special accommodation for the special nature of the operating system. Although the design follows the separation of concerns, no attempt is made to restrict the privileges granted to the individual parts of the operating system. The entire operating system executes with maximum privileges. The communication overhead inside the monolithic operating system is the same as the communication overhead inside any other software, considered relatively low.

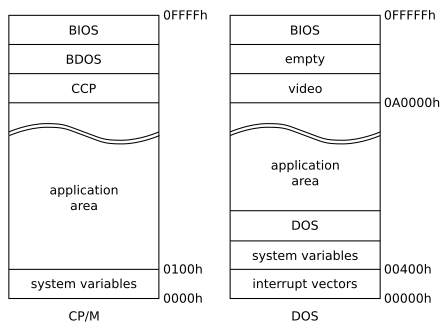

CP/M and DOS are simple examples of monolithic operating systems. Both CP/M and DOS are operating systems that share a single address space with the applications. In CP/M, the 16 bit address space starts with system variables and the application area and ends with three parts of the operating system, namely CCP (Console Command Processor), BDOS (Basic Disk Operating System) and BIOS (Basic Input/Output System). In DOS, the 20 bit address space starts with the array of interrupt vectors and the system variables, followed by the resident part of DOS and the application area and ending with a memory block used by the video card and BIOS.

Most contemporary operating systems, including Linux and Windows, are also considered monolithic, even though their structure is certainly significantly different from the simple examples of CP/M and DOS.

References.

Tim Olmstead: Memorial Digital Research CP/M Library. http://www.cpm.z80.de/drilib.html

A layered design of the operating system architecture attempts to achieve robustness by structuring the architecture into layers with different privileges. The most privileged layer would contain code dealing with interrupt handling and context switching, the layers above that would follow with device drivers, memory management, file systems, user interface, and finally the least privileged layer would contain the applications.

MULTICS is a prominent example of a layered operating system, designed with eight layers formed into protection rings, whose boundaries could only be crossed using specialized instructions. Contemporary operating systems, however, do not use the layered design, as it is deemed too restrictive and requires specific hardware support.

References.

Multicians, http://www.multicians.org

A microkernel design of the operating system architecture targets robustness. The privileges granted to the individual parts of the operating system are restricted as much as possible and the communication between the parts relies on a specialized communication mechanisms that enforce the privileges as necessary. The communication overhead inside the microkernel operating system can be higher than the communication overhead inside other software, however, research has shown this overhead to be manageable.

Experience with the microkernel design suggests that only very few individual parts of the operating system need to have more privileges than common applications. The microkernel design therefore leads to a small system kernel, accompanied by additional system applications that provide most of the operating system features.

MACH is a prominent example of a microkernel that has been used in contemporary operating systems, including the NextStep and OpenStep systems and, notably, OS X. Most research operating systems also qualify as microkernel operating systems.

References.

The Mach Operating System. http://www.cs.cmu.edu/afs/cs.cmu.edu/project/mach/public/www/mach.html

Andrew Tannenbaum, Linus Torvalds: Debate On Linux. http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/opensources/book/appa.html

Attempts to simplify maintenance and improve utilization of operating systems that host multiple independent applications have lead to the idea of running multiple operating systems on the same computer. Similar to the manner in which the operating system kernel provides an isolated environment to each hosted application, virtualized systems introduce a hypervisor that provides an isolated environment to each hosted operating system.

Hypervisors can be introduced into the system architecture in different ways.

A native hypervisor runs on bare hardware, with the hosted operating systems residing above the hypervisor in the system structure. This makes it possible to implement an efficient hypervisor, paying the price of maintaining a hardware specific implementation.

A hosted hypervisor partially bypasses the need for a hardware specific implementation by running on top of another operating system. From the bottom up, the system structure then starts with the host operating system that includes the hypervisor, and then the guest operating systems, hosted above the hypervisor.

A combination of the native and the hosted approaches is also possible. The hypervisor can implement some of its features on bare hardware and consult the hosted operating systems for its other features. A common example of this approach is to implement the processor virtualization support on bare hardware and use a dedicated hosted operating system to access the devices that the hypervisor then virtualizes for the other hosted operating systems.